In Aden, a small bomb-laden boat approaches the destroyer USS Cole at midship and the two suicide bombers detonate their explosives, killing 17 sailors and injuring at least 40 others.

The destroyer, en route to the Persian Gulf, was making a prearranged fuel stop, part of a Central Command (CENTCOM) initiative to improve relations with the Yemen government. The blast ripped a hole in the side of the USS Cole approximately 40 feet in diameter. The attack occurs without warning, and the Navy vessel was never warned to expect a terrorist attack.

The subsequent FBI investigation revealed that the USS Cole bombing followed an unsuccessful attempt on January 3, 2000, to bomb another U.S. Navy ship, the USS The Sullivans. In this earlier incident, the boat sank before the explosives could be detonated. The boat and the explosives were salvaged and refitted, and the explosives were tested and reused in the USS Cole attack.

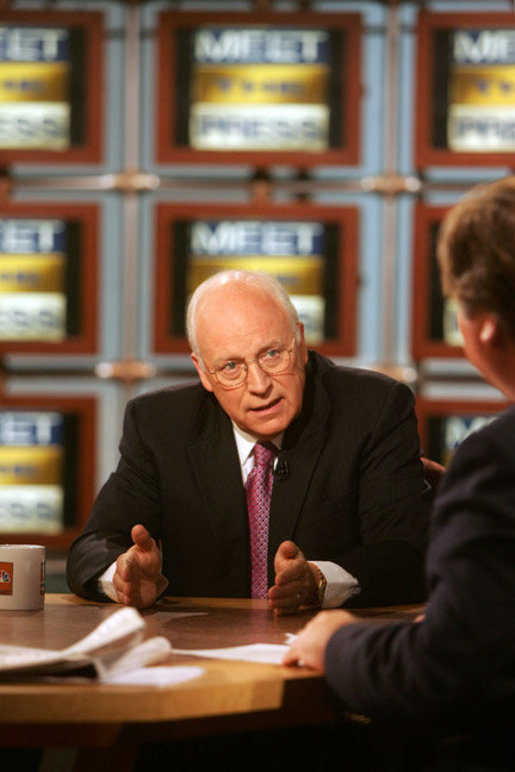

The “story” of the aftermath, favorable to a supposedly do-no-wrong FBI, is later told in Lawrence Wright’s Looming Tower, and the attack becomes an emotional debating point in the Bush-Gore presidential election. The outgoing Clinton administration is reluctant to retaliate against al Qaeda—the clear perpetrator—because an election is just a month away. But the Bush administration also does not take any military action, told by the CIA that it did not have enough “proof” of al Qaeda direction.

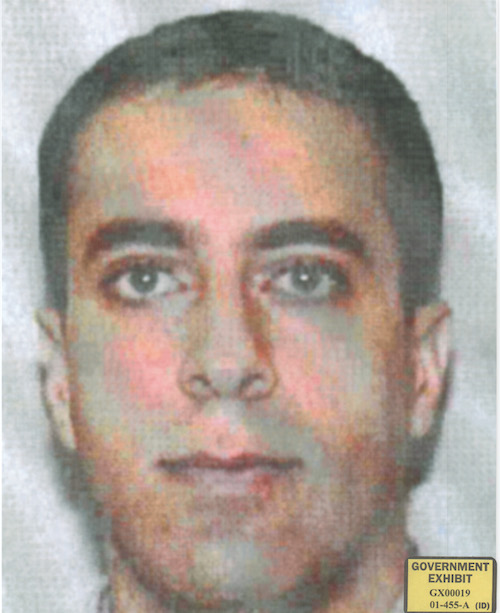

Yemeni authorities establish that Tawfiq bin-Atash (known as Khallad), who had been a trainer at an al Qaeda camp in Afghanistan and worked as an Osama bin Laden bodyguard, was not only one of the commanders but that he had been present at the January 2000 meeting of al Qaeda operatives in Malaysia. Khalid al-Mihdhar and Nawaf al-Hazmi, the San Diego duo who would go on to be “musclemen” on 9/11, were also present.

According to the 911 Commission Report (p. 191), back in Afghanistan, bin Laden anticipated U.S. military retaliation and ordered the evacuation of al Qaeda installations, fleeing to the desert area near Kabul, then to Khowst and Jalalabad, and eventually back to Kandahar. In Kandahar, he rotated between five to six residences, spending one night at each residence. In addition, he sent his senior advisor, Mohammed Atef, to a different part of Kandahar and his deputy, Ayman al Zawahiri, to Kabul so that all three could not be killed in one attack.

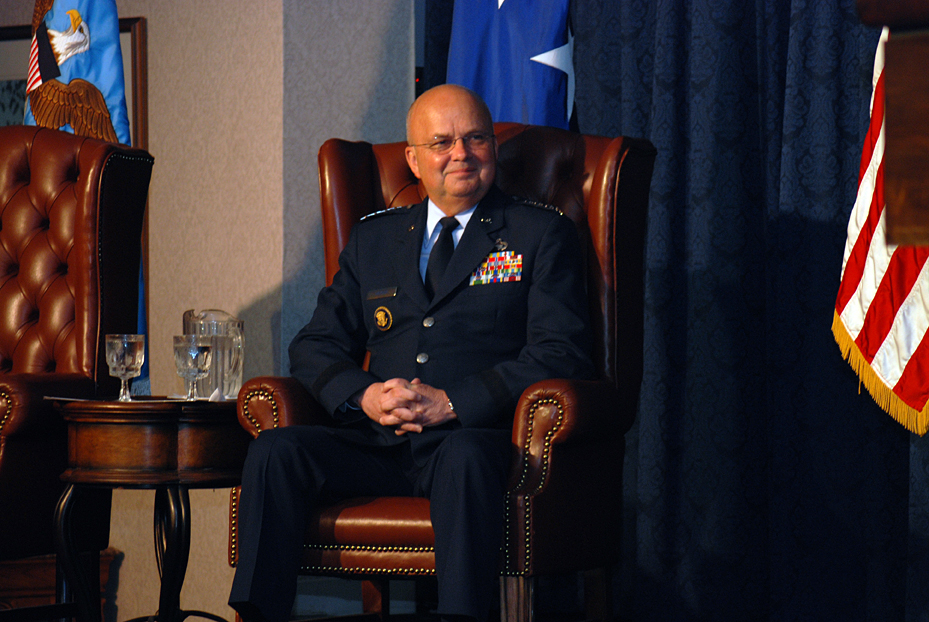

In writing his autobiography, George Tenet says that “neither our intelligence nor the FBI’s criminal investigation could conclusively prove that Usama bin Ladin and his leadership had had authority, direction, and control over the attack. This is a high threshold to cross… What’s important from our perspective at CIA is that the FBI investigation had taken primacy in getting to the bottom of the matter.” (At the Center of the Storm, p. 128).