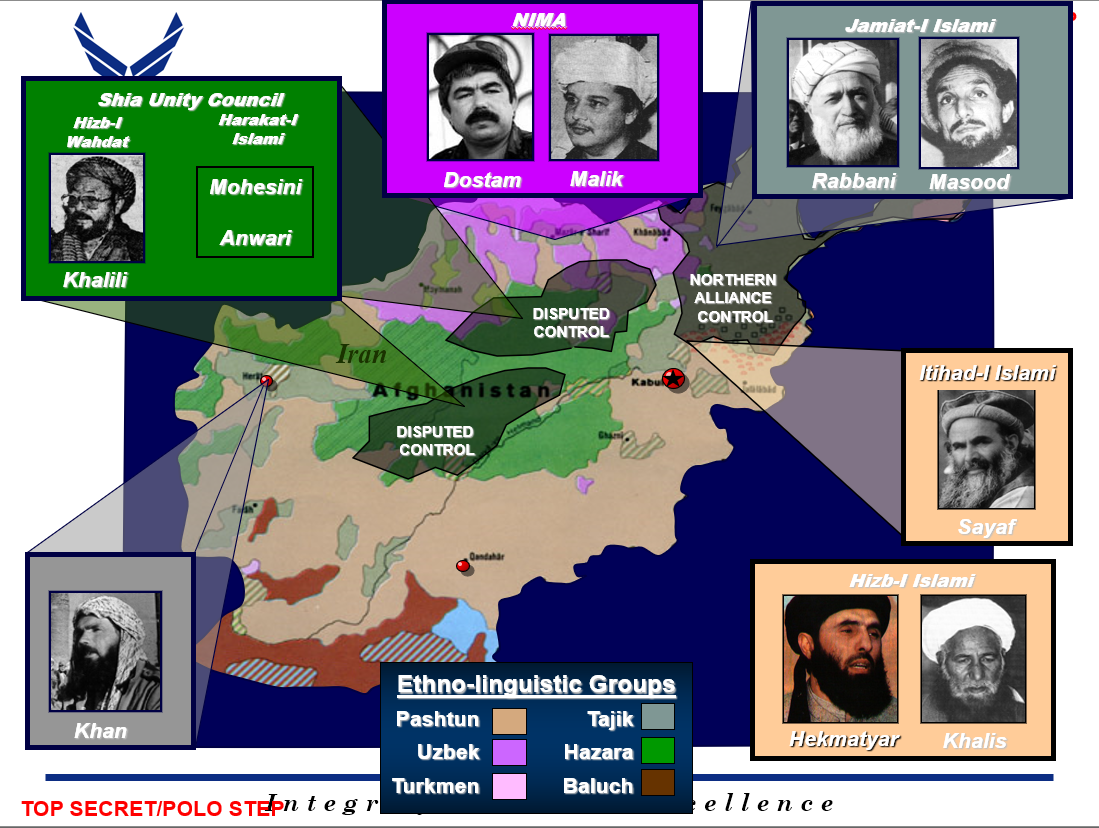

Afghan military commander and politician Ahmad Shah Massoud abandons Kabul and flees to the Panjshir Valley in the face of overwhelming Taliban forces, which had entered the Afghan capital city from the south.

Massoud had been a powerful mujahedin commander during the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan and was a leader of the so-called “Northern Alliance,” the United Islamic Front for the Salvation of Afghanistan.

The Alliance formed after the southern-dominated Taliban took over control of most of the country. Massoud’s forces were mostly Tajiks but included other non-Pashtun ethnic groups by 2001. Two days before 9/11, on September 9, Massoud was assassinated by a pair of journalists who blew themselves up during an interview. They are presumed to have been al Qaeda operatives.