U.N. weapons inspectors evacuate Iraq for the last time, removing with them a secret NSA telephone monitoring device that American agents had brought in under United Nations cover.

After weeks of disputes and obstructions by the Iraqis—stopping or interfering with inspections of “presidential sites” and other sensitive installations associated with Saddam Hussein’s protect—UNSCOM Chairman Richard Butler decides to withdraw all U.N. staff, setting the stage for American airstrikes.

President Clinton then signs the orders for Operation Desert Fox, and airstrikes against Iraqi targets begin just before 1 AM (2200 GMT on December 16). Desert Fox is aimed officially, according to the White House, against Iraq’s nuclear, chemical and biological weapons programs. British Prime Minister Tony Blair said that his country had also been left with “no option” but to mount the strikes. Russia and China condemn the actions and Russia recalls its ambassador from Washington. The next day, Russia recalls its ambassador to London.

Secretary Albright holds a briefing on Desert Fox and was asked how she would respond to those who say that, unlike the 1991 Gulf War, this campaign “looks like mostly an Anglo-American mission.” She answers: “We are now dealing with a threat, I think, that is probably harder for some to understand because it is a threat of the future, rather than a present threat, or a present act such as a border crossing, a border aggression. And here, as the president described in his statement yesterday, we are concerned about the threat posed by Saddam Hussein’s ability to have, develop, deploy weapons of mass destruction and the threat that that poses to the neighbors, to the stability of the Middle East, and therefore, ultimately to ourselves.”

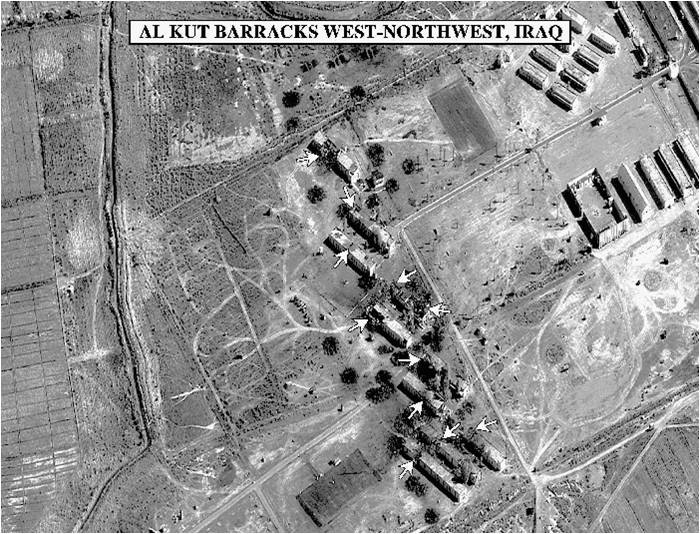

There are, of course, no real nuclear, chemical and biological weapons left, but then the actual targets of Desert Fox strikes are security-related facilities associated with Saddam’s presidential guards—with the hope that their destruction might provoke a coup or uprising. Inspectors don’t return to Iraq until 2003, in an eleventh hour effort to stave off the second Gulf War.